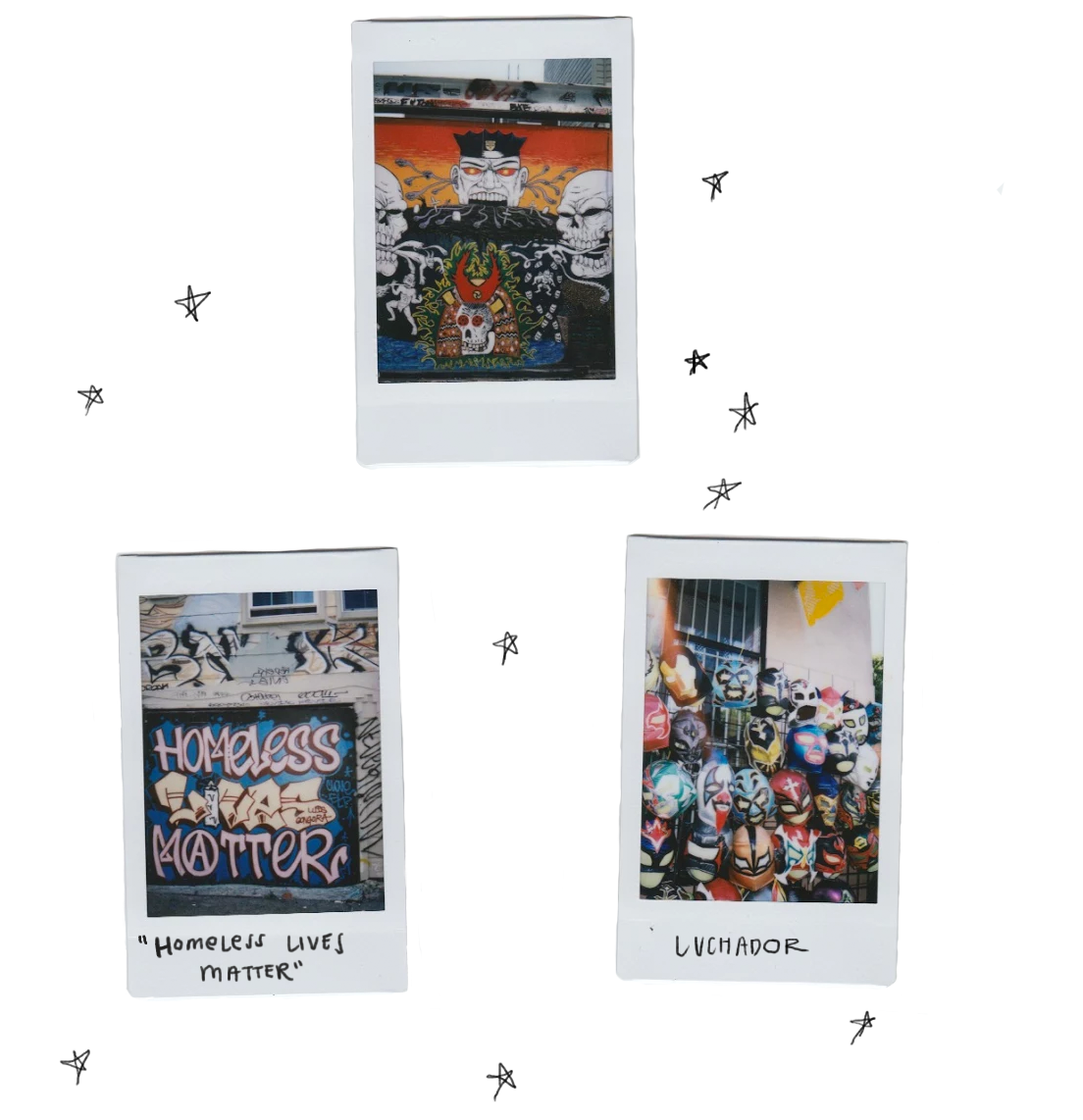

For the past seventy years, the Mission District has served as the epicenter of Latinx life and culture in San Francisco. Growing up as a child in the Bay Area, the Mission District was the place my family went to to stock up on groceries, pan dulce, clothes, money orders to send back home, and just about anything you can think of. It’s where they felt the most comfortable. It was no shock to see someone they knew while they were browsing for produce at La Loma. Because of the strong working-class Latinx population, much of the district’s character stems from the their vibrant culture.

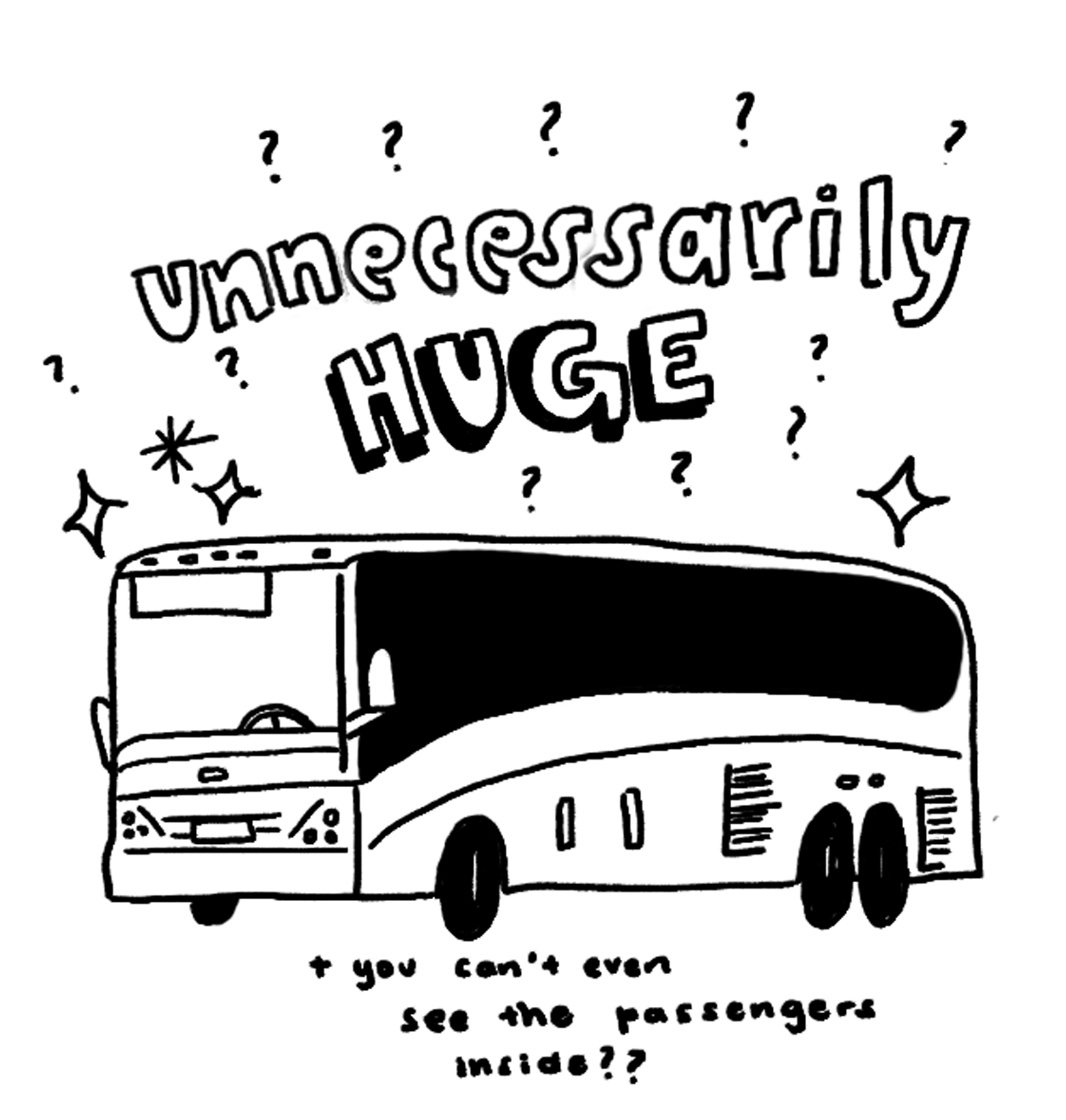

Since the late 1980’s, the Mission District has been subject to enormous change. Similar to the stories of countless neighborhoods across America, it has been experiencing a gentrification process in which a rise in rent and housing prices, redevelopment, lawful and unlawful evictions, and a shortage of rental units have forcefully displaced many low-income residents and left a significant number of them homeless. The current situation and conflicts of gentrification have risen as a result of the dot-com boom during the 1990’s to 2000’s, where many professionals in the computer, marketing, and business industries moved into San Francisco, changing the social landscape of the city. Walking down Valencia Street, corner bodegas and sidewalk sales transform into upscale coffee shops and pricey boutiques. Nowadays, the juxtaposition between the colossal, swanky tech shuttles roaming the street, transporting their VIP workers down south into Silicon Valley and the working class swarmed at MUNI stops getting to and from work is astonishing.

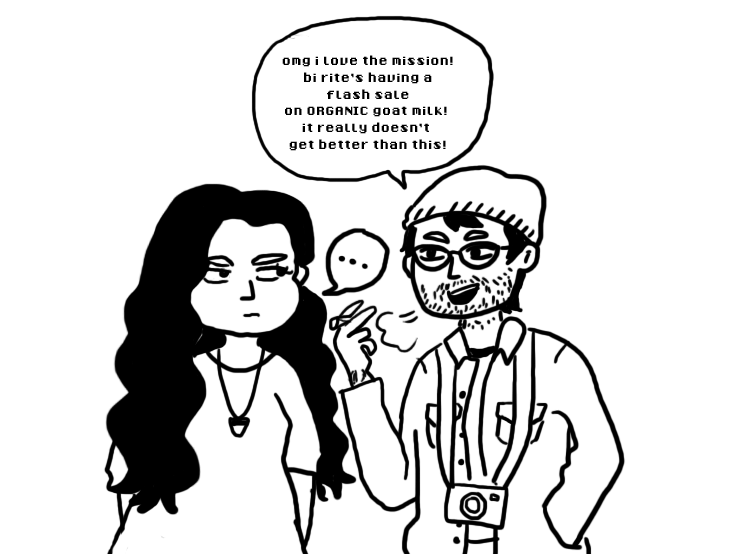

You would think that despite the differences in economic class between these two groups, their neighborhood would unite them, and the new residents would integrate themselves into the established Mission District culture and support it, or at least try to preserve it. But sadly, this is not the case. The Mission District, to me and many others, is very much segregated by class today. All the buzz and hype that the Mission is getting today, the businesses that are getting recognition for being “trendy” and “hip” are ones I hate the most.

To put it simply, it’s not the Mission I grew up in. I walk through the streets that have been tainted with new developments — new, sparkly sidewalks, plants and trees, cool businesses and ask myself, “Where are the familiar faces I grew up with?” I’m definitely not saying that people can’t start businesses and establishments wherever they choose, but at the same time, when they start these businesses, they replace the old, affordable businesses that actually once served the community. Tell me which working-class person can buy a $10 piece of chocolate without feeling guilty about it afterwards. It becomes quite alienating to the native community because they cannot enjoy the new developments and the luxuries that their Mission is experiencing. There’s nothing wrong with moving into a community, but tensions will definitely start to rise once the community notices that the influx of residents are not doing anything to support or preserve the culture and community that existed there prior. In fact, they’re doing the opposite— they’re contributing to the deterioration of the Mission.

What is left of the Mission is truly disheartening. Walk a couple blocks from the oasis of boutiques and artisanal vegan taquerias (really?) and you’ll see the Mission that was left behind. Our local government puts so much effort into redeveloping parts of the Mission, but for whom? The affluent, white San Franciscans are getting what they want, while problems like homelessness, drug abuse, and other issues still exist in the “browner” parts of the Mission. Friends always ask me to be their designated tour guide, and they are always enamored by the charm of Valencia, aka the poster child of gentrification, yet once we step outside of that bubble, into the parts of the Mission that I consider to be my second home, they get visibly uncomfortable and scared.

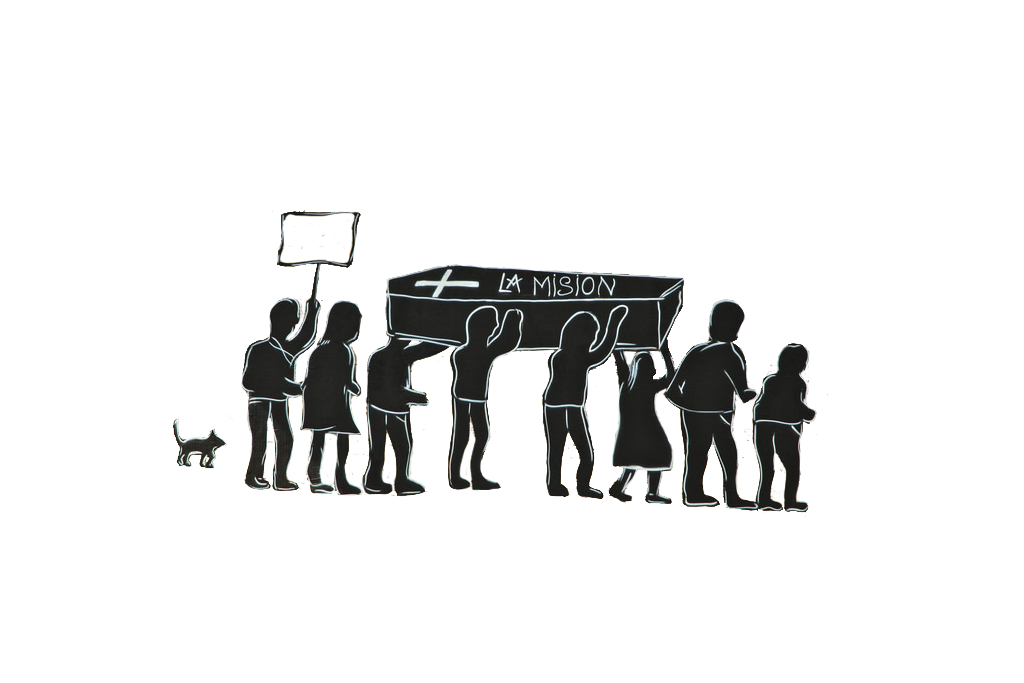

What was once a haven for Latinxs immigrating to the United States when their countries were experiencing socioeconomic instability and political strife, has now become a battleground, between the white and brown, between the upper and lower class, between new and old.

Do I want to see gentrification bleach out the Latinx culture I grew up with and turn the Mission District into a playground for tech workers? No, absolutely not. But do I want to see an end of gang violence terrorizing a community I love so dearly? Do I want to see people feel safer outside at night? Do I want to see a general economic growth in all parts of the Mission? Yes, absolutely! But is gentrification the best solution? In my opinion, it is too exclusive in that the advantages that come with gentrification cater to a specific population and offer few benefits to others. I want to see the Latinx community reap the so-called benefits of gentrification. But I don’t see that happening, at the moment. More than anything, it poses a major threat to the pre-existing Latinx population.

Take an argument that many pro-gentrification people like to use: safer streets. While it is true that the Mission District has experienced a drop in crime in recent years, it is at a very large cost. Safer streets requires a heightened presence of the SFPD, a police force with a long-documented history of racial profiling and discriminatory scandals, putting pre-existing residents of color in danger.

Another argument made by those who embrace gentrification is that it produces economic development through increased attraction to local businesses. But what happens when there is economic growth? The land where the growth is occurring becomes more valuable, which leads to higher housing prices and higher rents. Because the pre-existing residents of the Mission come from primarily low-income backgrounds, they cannot afford it, which makes them vulnerable to displacement. If they decide to bear the economic stress, they deal with an enormous rent burden, since more and more of their money is spent on rent alone. Even then, there are many cases of landlords who pressure the pre-existing population to leave, and evict them through laws like the Ellis Act in order to attract those with bigger pocketbooks. The Mission has the highest rate of evictions in the city and has seen a huge drop in Latinx households within the past decade.The effects of losing a home extend beyond what one may think. Residents lose their culture, their sense of belonging, they lose the community they once considered home. This is especially relevant in the United States today because there are a limited number of ethnic enclaves for Latinxs in the Bay Area. They do not have a lot of options in which they can relocate to, especially considering the fact that gentrification has only become more persistent and widespread throughout the nation within the past decade. While many may think of change as inevitable and something to embrace, I, for one, refuse to embrace the erasure and marginalization of my culture; I refuse to embrace the marginalization of Mission residents and businesses.

It’s time to start looking at the Mission for its people, not its economic potential, and that begins with advocating for marginalized people of color. Although many see gentrification as the cure for the Mission’s “problems”, the rate of displacement and dispossession of Latinxs and their culture can be minimized significantly with alternative solutions. Other forms of development in the neighborhood (besides new, hip businesses) such as the implementation of more affordable and subsidized housing and fighting for tenant rights can reverse the cultural damage the influx of white and affluent residents has caused. There needs to be a lot of work done before we see the economic flourishing of the Mission affect all social groups equally. There needs to be a productive dialogue of gentrification. For example, local government should allow community members to form a panel and/or provide input on policies and investments they would like to see in the Mission.

Instead of only responding to displacement when there are complaints and protests by citizens, proactive enforcement of anti-displacement policies should be funded by the local government. Corporations also must be held accountable for their role in this phenomenon. Although tech and large real estate developers such as Zephyr Real Estate, SOMA, and Google fuel the erasure of Latinxs by being complicit to the profit motive for landlords to push people out, politicians that represent the communities hurt by them continue to take their donations. (Looking at you, Scott Wiener, David Chiu)

As individuals, we all have a responsibility when it comes to fighting gentrification. Educating ourselves of tenant rights so we can detect the problems that affect our community, being conscious consumers and frequenting local businesses that have been around for a while rather than only supporting newer establishments, direct action in the streets, uniting with and supporting agencies and grassroots organizations that are dedicated to helping the oppressed (Causa Justa: Just Cause, San Francisco Tenants Union, and the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project are some of my favorites). As for San Franciscans, learning about the history of our city, from the Ohlone and other indigenous peoples to the present are some of the many steps we can take to understand the roots of gentrification and the importance of the Mission District to Latinxs.

I’m a firm believer of the importance of the vote and I encourage San Franciscans to tap into that power of voting. It’s crucial to look into the campaign platforms of politicians running for office. Standing behind candidates like Hillary Ronen and Jane Kim who center their work on affordable housing and tenants rights should be something anyone who wants displacement to end should be considering this upcoming election.

It’s time to wake up and leave behind our indifferences to the evictions of our Latinx families in the Mission neighborhood. Gentrification isn’t natural, and displacement is not inevitable. When work together, we become stronger, and we can change the course of history for Latinxs in the Mission.